To see the influence of technamagix on the ryû-ga, first an understanding of the anatomy and ecology of the genus Insecta Lepidoptera Yamatonis, or more commonly: "Yamato moth", is required. And luckily, I was able to acquire a truly rare document just recently: The Yamato-Ga-Daijiten 大和蛾大事典 ("The Great Encyclopedia of Yamato's Moths"), fully furnished with extensive though archaic scientific observations, diagrams, and hand-drawn images; a true pleasure to share.

- a 143 GE (Age of Gears and Elements) reprint of the Yamato-Ga-Daijiten, woodblock print with elaborate Middlish binding.

Moths and the Yamato Culture

Now, I will present an overview of the domestication and exploitation of Lepidopter Yamatonis for resources by the Yamato people and their ancestors in an upcoming section, but before I get to that, and indeed before I begin the analysis of the moths' biological and ecological traits, a part of this chapter should be set aside to, in the briefest of terms, discuss their influence on the culture of the Yamato people.As a scholar, not only of magic and the sciences, I, Rickard Leeuw, have spent many years in the Yamato Mountain Range, experiencing the intricate culture of its people and researching the fascinating flora and fauna of its slopes, sheers, caves, and valley. Rarely have I seen such an abundant treasure trove of nature, and among the many bounties it has to offer, few are as curious as the great moths of Yamato. Indeed, one may argue that the very roots of the Yamato people are so deeply entwined with these creatures that there is no separating them anymore and discussing one means discussing the other as well.

In my experiences with Yamato culture, I have time and time again heard wondrous tales spun around encounters with moths, beautiful poetry and enchanting song. In fact, in the popular art of renku 連句 (linked verse), in which a set number of haiku 俳句 (single verse poems with a set number of phonetic syllables) are joined together into one poem, usually with each verse originating from a different author, traditional themes are the four seasons, the five elements, and the moths of Yamato, and renku rarely ommit the last one, likely because the intense scent of the gentle and docile murasaki-ga's 紫蛾 ("purple moth") moth dust is strongly associated with spring, and the deadly spectre that is the yarenma-ga 夜連魔蛾 ("night carrier spirit moth") is usually associated with winter, death, decay, and sleep.

As this is my codex and I have no editorial obligation other than to stick to what is true or at least what is plausible, I shall take the liberty to share a number of poems and short stories that, in my humble opinion, convey some of the concepts and ideas the Yamato people have attached to the moths to better convey the extreme cultural significance they hold. You may shirk such practices should you be very scientifically minded, but if you do, dear reader, I caution you to always keep your horizon as broad as possible and never to shun the arts, for as we are beings with ambition, with hopes, and dreams, in short: beings with souls, artistic expression will always be a drive that encourages us to move forward, even scientifically. I have no doubt that the deep cultural significance of the moths was what first inspired the Ryoku'u, now known as Greenhorns, to perform their technamagical experiments on them, creating the mighty ryû-ga, which in the end is the subject I wish to prepare you for with this intermediary chapter.

Among the many songs about the moths of Yamato, I feel compelled to first share the same-named song "The Moths of Yamato", which was translated into the common Middlish tongue (with some liberties) in 60 AA (Age of Awakening) by the fabled Mad Magus Hestia. A lovely contribution, though perhaps less than adequate to compensate for certain other actions she performed in her later life, but I digress. The translated version of the song goes as such:

While there is much to unpack here on a literary level, I will content myself to pointing out the duality of the murasaki moth and the yarenma moth depicted in this song: the winds are wily but conversely also steady because the theme of moth dust it is attached to can both apply to the sweet aroma of murasaki moth dust and the deadly narcotic property of yarenma moth dust. The duality of the beauty and danger of Yamato moths is a central theme of not only this song but many others and is tied deeply into the perception of the Yamato Mountain Range, which offers breathtaking but often treacherous terrain. The association of murasaki moths with the sun or day time and yarenma moths with the moon or night time is a common theme in Yamato literature and poetry, and both sides can be symbolic for each other (yarenma moths for the moon, the moon for yarenma moths, and so on).Flow in wily winds,

As steady as dust will glitter on

And wings that flap along

Are dancing to this song.

Patterns in ashen tint:

Times sun, times moon may fall in line

And gather powdered souls of mine

And build a golden shrine.

The golden shrine is sometimes thematized and comes from an ancient tale called "Yanagi no Ôkoku" 柳の王国 ("The Willow Kingdom"). In his seminal work "A Comparative Study of Yamato Folklore", Hans Walger presents a summarized version of the story, short enough to present here:

When the descendants of the Kokusei1While this tale superficially does not seem to have much to do with the moths of Yamato themselves, it is actually one of the oldest stories of the Yamato people, and over the course of millenia it has been modified and amended many times via oral tradition. This is significant because throughout the ages, the role of moths in the tale of the Willow Kingdom has grown more and more. These days common Yamato folk generally think that the Willow King was the first Yarenma moth and influenced King Glam Shen by giving him terrible dreams that twisted his mind. Additionally, many more tales arose from this one like the one of the clever prince Yanagi Hôtaru, who tied one hundred and six murasaki moths together with string to carry him up to the Dairintaisha shrine on new years day but then got blown away in a storm because he had angered the spirits with his disrespect.The Kokusei, short for Kokuyôsei 黒妖精 ("Black Elves"), are known as Swartalben in the Middlish tongue and were one of the races of men that lived in the Nine Realms before the War that Reshaped the World.traveled further and further east, they found before themselves a majestic mountain range, full of strange wonders and treasures. Their greatest chief Glam Shen bade them to scale the mountainside and find out what was on the other side, for his people had become nomads of the land, moving here and there, never staying in one place, even though his ancestors had once built great halls in the mountains of Swartalbaheim of the Nine Realms. Glam Shen had the gift of vision, and he saw in these mountains a new home for his people, and so he scaled them with great determination. As he traveled through the lush forests of the slopes, he found delicious round fruits with a thin, yellow rind and a sweet, juicy core growing on trees everywhere, and he named it nantama, and its nourishing flesh allowed his clan to roam the mountain range far and wide. As they climed the tall peaks, they found the great valley, protected by mountains to all sides, and they called this land Yamato.

And on the slopes and sheers of the Yamato Mountain Range, Glam Shen discovered the strange creatures that we call murasaki moths today. Sweet was the scent they spread throughout the land, tufty and bright purple was their moth fur. His tribe quickly took to hunting the creatures, migrating through the edges of the valley, also making sport of goats and bayô, the horned goat horses of the Yamato Valley. As they traveled along the slopes and cliffs, they rediscovered their ancestors' great talent for mining and working metals, and they found many treasures hidden in the mountains, including a most precious yellow metal that gleamed beautifully: gold.

"What a wondrous treasure! Surely this gleaming metal is the stuff from which the wheels of the Daihô2The Daihô 大法 ("Great Law"), also known as Dharma in the Seventeen Yonder Islands and as the Great Clockwork in the Middle Lands, is what the Yamato people call the basic truths of the universe or the nature of the clockwork.are forged..." Glam Shen spoke. "We shall mine it and sell it to the Midgardmen, who built houses of stone and till fields in the earth, for surely they will covet it. And with their help we will carve out our own kingdom here!"

And he would have his men mine great quantities of gold and bring them to the Middle Lands where he convinced all the descendants of the Kokusei to join his new kingdom and bought manpower and technology from the Middlish men to support the founding. It did not take long for the people of Glam Shen to build houses of stone and wood themselves and till fields in the fertile valley. And they caught many goats and bayô and murasaki moths and held them in pans and fields, harvesting their milk, horn, flesh, and fur, and in time also the swamp gas that the moths carry in their bellies for lamps. Soon the new kingdom named Yamato was prosperous beyond ken.

But in his latter days, Glam Shen became restless and spoke of spirits of the valley that he had angered. He wandered for many hours each night and his subjects knew not where he went, only that he was somewhere in the thicket of willows by the mountainside. Some began to jest that he was going to treat with the Willow King, but their mockery was short lived for one morning after being gone for many days, he returned from the woods and his hair had become as white as winter snow, and his eyes glowed blue like sapphires with fire behind them. His people feared his new form, and he bade them to gather much gold and wood and to climb to the tallest peak and erect a great shrine in honor of the Daihô and clad it in golden plates, so it would glimmer and throw the sun's light far and wide for all to see. Glam Shen had become the world's first Yasha3This statement is actually apocryphal since the Angel Smiths have suffered from spellblight since before the War that Reshaped the World. The misunderstanding is based on the fact that for the longest time, people were under the impression that that was just coincidentally a natural look for their kind..

The construction took many decades, and many people died during the project, but in the end the golden shrine was completed, and he named it Dairintaisha 大輪大社 ("Grand Shrine of the Great Wheel") and proclaimed that on the first day of the year, the king was to visit the shrine and pay homage to the Daihô, and so he did and his successors as well. The Shrine was struck by lightning ten times on occasions during which he visited it, and despite taking severe damage and requiring serious repairs that were perilous and expensive, Glam Shen himself was never harmed, and many rumors and terrible stories spread that he had made a contract with the Willow King, selling his soul to the Willow Kingdom, which had turned his hair white and his eyes blue and forced him to have the shrine built. But for what he had paid this price none knew, though everyone speculated much on it. When he died, no King after him dared to ommit the annual shrine visit, fearing some unknown contract with the spirits may be broken on that day, and the custom continued for many centuries.

Basic Information

Anatomy

From the three moth sub-species, murasaki-ga, yarenma-ga, and sensô-ga, murasaki-ga is therefore the oldest archetype. Both yarenma-ga and sensô-ga are mutations that were directly caused by human influence over the previous millenia; one accidentally, one through breeding. The YGD offers many detailed drawings of all three types of moths, which is quite fortunate since sensô-ga are under urgent species protection by the Yamato Kingdom and yarenma-ga are so dangerous that the perils of field research are quite discouraging to most sane individuals. Though very different in morphology, the basic anatomy of Yamato moths is very similar:

- All three types have the same kind of light-weight, crab-like insect musculature.

- All three have similar types of hemolymph distributed by a sort of vascular system and pumped by a heart-like muscle, which most resembles the blood-system of a fish.

- All three have intricate book lungs(see: Sidebar > Useful Information) attached to the inner part of the underside of their wind sacks.

- All three have similar wing structures.

- While differing in number and structure somewhat, the extremities of all three use chitin exo-skeletons.

- All three share a number of sensory and internal organs.

Now, at this point it comes to mind that I may have been less than consistent in my naming of these creatures - is it murasaki-ga, or murasaki moth? Well, the answer is both; ga 蛾, as you most likely know, simply means moth. I realize that I should probably just stick to writing moth instead, but when speaking, most people studying moth lore have the tendency of saying "murasaki moth", "yarenma", and "sensô-ga". This is likely due to "murasaki moth" rolling better off the tongue than "murasaki-ga" while the opposite is true for "sensô-ga" as opposed to "sensô moth", which is somewhat like saying "war creature" instead of "war-beast". As for "yarenma", well this one is again related to Yamato culture, because Yamato people will usually not say "yarenma-ga" but just "yarenma". This comes from the creature being more of a bad spirit or demon than an animal in the populus's mind. To maintain a modicum of consistency, I will call all moths by the same naming convention within each paragraph.

Moth Organ Commonalities

Many organs of Lepidopter Yamatonis are in their construction and function very similar between the three types. The YGD offers the following depictions of moth organs:Gayoku 蛾翼 ("Moth Wings")

The filament structure of the chitin is actually shown in the sketch and is relatively representative, albeit crude, of the actual structure of the material. Modern research has shown that each protein filament is arranged as a nano tube encased in more filaments, creating an incredibly durable biomaterial.

When the moths are at rest in windless areas such as caves, they sometimes slowly move their wings up and down to fan air into their book lungs.

Fudai 風袋 ("Wind Sack")

- Catching the wind (hence the name "wind sack") by significantly increasing the creature's surface area, reducing the energy required to stay aloft, even enabling it to sail without wing flapping if the wind is just right.

- Breathing. Close to the body, complex book lungs are embedded into the floating fins, acting much like a fish's gills. As the wind ariates the book lungs below the floating fins, air passes through the book-like layers of trachea, oxygenizing the hemolyth of the moth. The sketch presented here reads from top to bottom: wind sack, gill slits, and book lung.

Funshokkaku 粉触角 ("Dust Antennae")

The dust antennae, as I previously stated, have many hair-like extensions protruding from them. The sketch of the YGD describes these as funbenmô 粉鞭毛 ("dust flagella"), a logical naming convention as the flagella are capable of slight motion in addition to the antennae's mobility. A second close-up sketch of a single flagellum shows that it is completely covered in pores that can release large quantities of moth dust. The composition of the dust depends on the type and gender of the moth. The famous murasaki moth dust smell coveted by the Yamato people is actually produced by the male murasaki moth, whereas the female dust is less fragrant to the human nose. The yarenma moth dust, of course, while still serving as an attractant for mates (just as for all Lepidoptera Yamatonis), is also a powerful narcotic and extremely dangerous to inhale for any mammals.

Fubuku 浮腹 ("Floating Belly")

The sketch reads (starting with the title on the top left and going clock-wise from there): floating belly, floating belly lining, swamp gas, swamp gas germ fluid, escape sphincter, insect fluid system, insect skin, esophagus.

The esophagus transports biomass into the floating belly, where the "swamp gas germ fluid", a sub-species of archaea(see: Sidebar > Useful Information) organisms, digests it to provide energy to the body, producing large quantities of methane gas as a side product. This gas bloats the floating belly, allowing the moth to maintain a large abdomen with a comparably low density. This has allowed the moths to grow considerably larger without being grounded by the square-cube law since the larger size makes it easier to be carried by the wind and also deter predators. Contrary to the original belief of the YGD's author, the methane does not provide any considerable lift (a few grams worth at best), so the name "floating belly" is somewhat apocryphal.

The so-called "escape sphincter" is connected to a tube-like growth that in turn connects to the floating belly and a second sphincter. Through this, methane can escape in case too much pressure builds up, though the floating belly is extremely tough and flexible and can expand to many times its deflated size. The murasaki moths use this sphincter to release methane blasts that can propel them upwards quickly, a useful escape mechanism. Humans have also domesticated murasaki moths for, among other things, extracting their gas, which is used in gas lamps and alchemy (for more on this see the segment on domestication and exploitation). In yarenma moths, this has evolved into a vent that blows over its antennae to promote dust dispersal, and sensô moths only use their escape sphincters to regulate methane pressure in their bodies and expell undigestable matter.

An additional sketch of the moths' eyes is included in the YGD, but I will attach that one to the upcoming section on the perceptory organs of Lepidopter Yamatonis.

For now I shall move on to the morphology of the different types of this fascinating species.

Comparative Morphology

The different types of Lepidopter Yamatonis, namely murasaki-ga, yarenma-ga, and sensô-ga, have somewhat varying morphology, starting with their notable differences in size. The following size comparison chart should prove more than helpful, as in addition to a scale it also shows a silhouette of an average human man next to the different types of moths, better highlighting their actual sizes:From smallest to largest creature, the lables on this chart read: murasaki-ga, human, yarenma-ga, and sensô-ga. As seen here, the size of the common murasaki-ga is comparable to that of a small dog, the yarenma-ga to a fairly large human, and the sensô-ga to a female mammoth. These, of course, are average sizes for the species, and moths can grow considerably larger or smaller than this in specific instances.

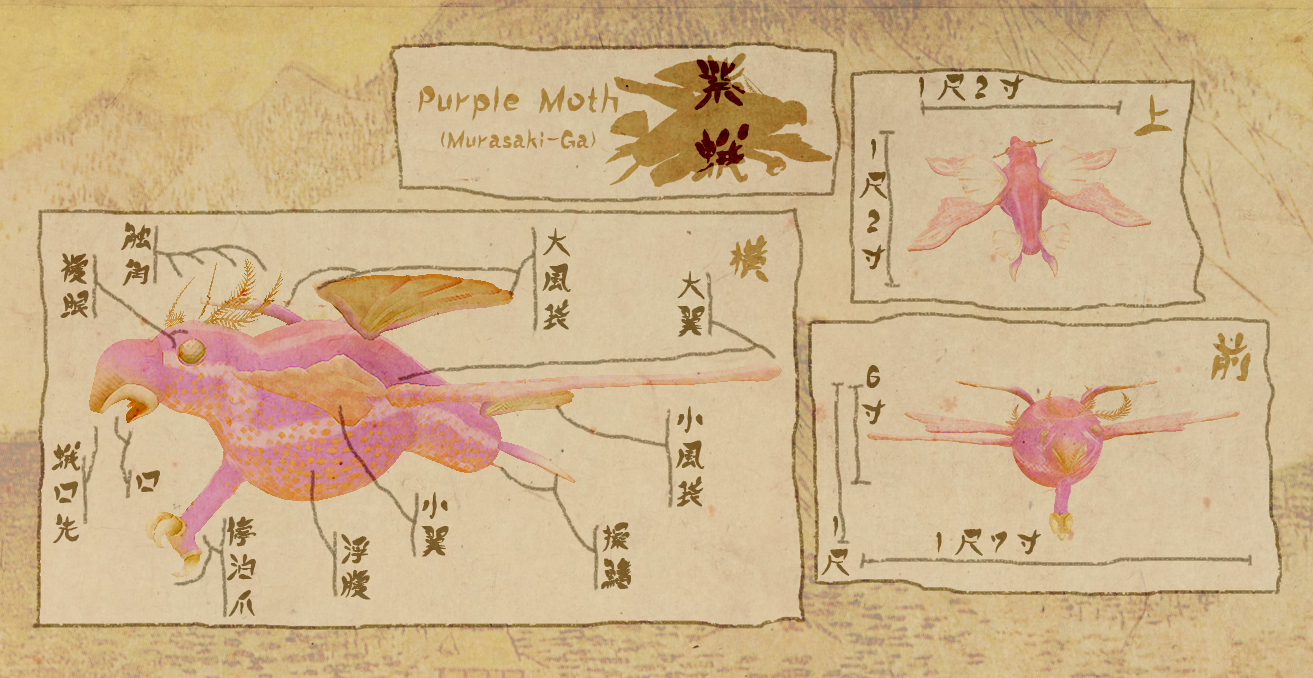

Morphology of the Murasaki Moth

From the top-left-most lable of the main image, the descriptions of the murasaki moth's morphology in this YGD drawing read (going clock-wise from there):

Compound eyes, bug antennae, great wind sacks, great wings, small wind sacks, maneuvering fins, small wings, floating belly, mooring claw, mouth, moth proboscis.

The mooring claw of the murasaki moth is used to tether itself to the ground when eating shishisô 四指草 ("Four-fingered Grass") (see also: the segment on dietary needs & habits) or similar food that potentially exposes it to wind, as it would be blown away otherwise. They also use it to tether themselves to cave walls at night.

The prominent proboscis is used to stroke the fur of the shishisô, and loosen it out of its compacted form to consume.

Because of the comparatively large size of the floating belly, the surface-to-density ratio of the moth is so favorable that very little energy is required to fly, especially if even soft wind is blowing. The wings are often used more to steer than to lift. Because the creature does not possess a spinal cord, its range of body movement is limited and it instead turns its whole body using aerial maneuvering.

The two smaller pictures show the measurements of the average murasaki moth. These are given in imperial units: shaku 尺 (approximately 0.30 meters) and sun 寸 (one tenth of a shaku). By this reckoning, the measures of the murasaki moth using the Altonar metric system are as follows:

36cm small wing span, 51cm great wing span, 36cm body length including fins, 18cm body height without mooring claw, 30cm shoulder height with mooring claw (implying an approximate arm length of ca. 12cm).A note here: the Yamato characters on the two small sketches simply indicate that the top one is a top view of the animal, the bottom one a front view of the animal.

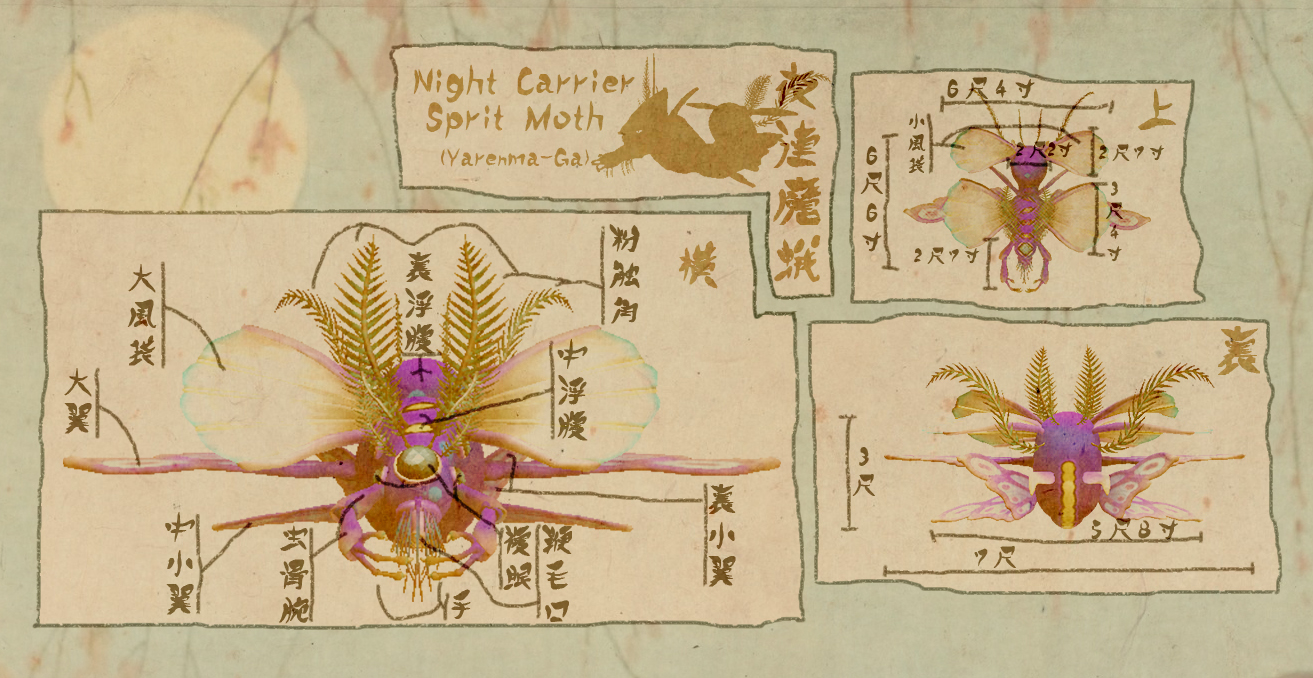

Morphology of the Yarenma Moth

The morphology of the yarenma moth varies significantly from that of its smaller murasaki moth brethren. It is much larger and possesses a total of two floating bellies, a configuration shared by the sensô-ga. This second floating belly actually does exist in the murasaki moth as a deflated proto-organ that was likely a back-up floating belly in the ancestor Lepidopter Yamatonis Murasakis Protogenius, which in time turned into an unused appendix in modern day murasaki moths.

But before I go into more detail, let us discuss the question: why is the yarenma moth so different from its cousin in appearance? Well, the answer to that is connected to the Willow Kingdom story. When the tribes of the Kokusei's descendants traveled through the Yamato Mountain Range, ever prospering, they nearly hunted the murasaki moths into extinction. These were relatively peaceful and passive, not having any natural enemies, which made them easy prey for the humans. Over several thousand years, random mutations to their genome lead to their adaptation into the form we know as yarenma moth today.

The reproduction of those moths who were best suited to repell humans was fostered by this, and the traits became more and more pronounced over a long period of time: additional and larger antennae for keener senses and the vaporization of heavy concentrations of moth dust, which itself mutated first to cause nausea in mammals, then to induce sleep and coma; relocation of the escape sphincter to aid dust dispersal, evolution of the mooring claw into two small arms with filigrane hands able of plucking nantama fruit, the higher nutritional value of which aided the increased body size, and lastly a mouth ringed with flagella, that can move freely and serve as haptic sensory organs, and a long, barbed tongue, both capable of licking through the slightly tough skin of the nantama fruit and of gouging flesh out of comatized victims of the moth dust. Over the course of four centuries, this type of Lepidopter Yamatonis became so deadly to humans that they were able to thrive in several cave regions of the great Yamato Mountain Range.

Now, the main drawing of Yarenma moth morphology in the YGD reads as follows (starting with the center lable above the abdomen and moving on clock-wise):

Hind floating belly, dust antennae, central floating belly, hind small wings, flagella mouth, compound eyes, hands, bug bone arm, central small wings, great wings, great wind sack.

The first size chart contains the additional body part lable for the small wind bag.

In total, the yarenma moth possesses four hind small wings, two central small wings, two great wings, one set of great floating fins, one set of small floating fins, two arms, two hands with four fingers each, one central and four lateral compound eyes, six antennae on its head and four on the back of its hind floating belly, two large, segmented floating bellies, and a mouth opening with haptic flagella around it.

The size measurements given translate as follows:

A body height of 90cm, a small wing and small floating fin span of 176cm, 212cm great wing span, 200cm body length, 193cm great floating fin span, 81cm small floating fin width, 103cm great floating fin width, and 81cm arm length.

Morphology of the Sensô Moth

The sensô moth is the prototype of the much larger ryû moth which I will discuss at length in the following chapter. Interestingly, this type of Lepidopter Yamatonis is, like the yarenma moth, a product of human influence. However, its significant differences to the regular murasaki moth were cultivated using selective breeding to increase size; but more on that in upcoming segments about domestication and species exploitation.

For now, let us focus on the general morphology of this type of moth. For one, the sensô moths are the largest of their kind, coming close to the size of northern mammoths. At the same time, their large floating bellies reduce their overall density-to-volume ratio to such low levels that they weigh about as much as a grown human man. This means that the ancient moth riders that rode sensô moths into battle during the Age of Heroes generally had to be small and slim to not overburden their mounts, though sensô moths do have quite a bit of capacity for extra weight.

The lables on their morphology drawing read as follows (starting with the outermost left lable and going clock-wise from there):

Hind wings, hind floating belly, wind sack, moth antennae, wind sacks, mouth, compound eyes, moth legs, side wings, forward floating belly.

While the front legs are simple bug-like legs for landing, the hind legs have flat claws that work like the murasaki moth's mooring claw. Both legs have light-weight chitin exo-skeletons and insect muscle inside and can be used to provide initial lift when taking off or to anchor the moth against wind. The antennae are named "moth antennae" instead of the previous "dust antennae", because sensô moth dust barely has any smell and is therefore not so prominent to humans, but it still serves to attract mates.

The measurements of the sensô moth read as such:

400cm general wing span, 285cm frontal floating fin span, 200cm body width, 209cm body height, 179cm hind floating belly height, 206cm hind wing width, 97cm floating fin length, 91cm floating fin width, 91cm forward floating belly length, 106cm mid segment plus hind floating belly length, 248cm side wing width, 60cm leg height, 91cm head length and 60cm head height.

Biological Traits

Male and Female Murasaki Moths

- Male

- Slightly larger.

- Much more fragrant moth dust.

- Female

- More vibrant wing patterns.

- Slightly thicker fur.

Male and Female Yarenma Moths

- Male

- Slightly smaller.

- More potent narcotic dust.

- More aggressive

- Female

- More vibrant wing and abdominal patterns.

- Slightly larger.

Male and Female Sensô Moths

- Male

- More complex abdominal patterns.

- Stronger wings.

- Female

- More vibrant wing patterns.

- Thicker fur

Genetics and Reproduction

The steps that follow next are sketched out in the YGD as shown in this drawing: the upper text block reads:

The female becomes pregnant once the antennae touchIn addition to their regular functions, the antennae also serve as a sexual organ and can produce a special variety of moth dust at times that carry the male's genetic material. This passes through membranes in the female's antennae and mixes with her own genes. Naturally, the text in the YGD is not that biologically specific since the concept of ribogenetics was not known at the time, except perhaps to the inventors of that branch of science themselves (I speak of course of the Greenhorns).

Once the female has been impregnated, egg sacks begin to form near her escape sphincter in her floating belly. Two to seven sacks form, each containing up to twenty eggs. The text on the sketch reads:

The eggs are raised by the escape sphincter of the floating belly.

At the time of birth, the pressure of the swamp gas is utilized to send the eggs flying from the escape sphincter. The surviving eggs will grow up as caterpillars.

The moth caterpillars are usually kept in their birth cave, where the moths that share the living space will regularly stockpile food (usually nantama fruit flesh or shishisô fur), which is then consumed by the caterpillars that litter the floor. Birds will venture into the caves and sometimes succeed at snatching them up, but usually the moths use their mooring claws to chase them away (or in the case of yarenma moths just their narcotic dust, after which the birds become food in turn).

Once the caterpillars have eaten enough, the floating belly forms first, until they float to the ceiling of the cave, where they form a cocoon to metamorph in. During this process, the floating belly remains unchanged and attached to the cocoon, until the developing moth grows around it.

Growth Rate & Stages

- Murasaki moths → about four lunar cycles

- Yarenma moths → about one-point-two years

- Sensô moths → about three years

Because the color perception of murasaki and sensô moths is limited, the shape of their patterns is more important for mate selection, while bright colors have a strong effect on yarenma moths, who have color perception that may actually surpass that of most humans.

Ecology and Habitats

Yarenma moths live in caves and only come out at night. The reason for this is that the narcotic molecules in their moth dust are quickly denatured by UV radiation, thus they stay in dark places during the day where their defense remains effective. When outside their caves, the landscape will likely be that of a forest or grove containing the widely spread nantama trees of the Yamato Mountain Range. When they eat the fruit, the seed doesn't leave their floating belly intact and is largely digested and tourned into nourishment and methane, however, some seeds tend to catch in the flagella around their mouth hole and later scatter around the ground, which further proliferates the nantama fruit throughout their habitat.

There is no information about the natural habitats of the sensô moth in the YGD, which is, of course, only natural, since they did not have one, being domesticated creatures created through extensive breeding. However, since the YGD was written, sensô moths managed to spread into the wild in two locations, though in very small populations. They tend to live in groves with large trees, of which they eat the leaves.

Dietary Needs and Habits

Biological Cycle

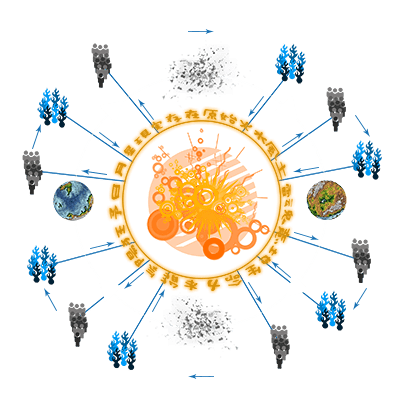

This picture of the seasonal eating habits of Yamato moths is arranged as such: Top left → winter 冬, top right → spring 春, bottom right → summer 夏, bottom left → autumn 秋.Murasaki moths are most active in summer and fall when shishisô is most readily available. In winter, they retreat into caves and cling to cave walls with their mooring claw, beginning their hibernation cycle. During this time, the archaea bacteria rich fluid in their floating bellies that is responsible for methane production congeals, rendering the bacteria inert, while small glands in the organ's lining release a different bacterium that slowly converts the stored methane into energy to survive the winter. Before beginning the hibernation, the moth colony sharing the cave will gather a small store of shishisô fur so they can consume it in spring to build their methane bubble back up. In spring they switch their diet to mountain flowers. The rich nectar of the flowers is used to produce their fragrant moth dust used to attract mates, which is probably the reason the smell is so strongly associated with spring by humans. Personally, I have found the odor to be quite envigorating, reminding me of the bracing effect of mint or oxigen-rich, cold air, though the smell itself is less minty and more reminiscent of flowers and freshly cut grass.

Each season is divided into the three moth types; going clockwise: sensô moth, yarenma moth, murasaki moth. The foods displayed are (starting from top center): feed for domesticated moths, various bird species of the Yamato Mountain Range, various mountain flowers, feed, nantama fruit, shishisô, feed, nantama fruit, shishisô, feed, goats and mountain lions.

The yarenma moths, on the other hand, are active during the entire year. They leave their caves less often in winter and become notably more predatory. Though they, too, create a small storage of nantama during autumn, it usually isn't enough to last them through the entire winter, which leads to them flying out of their caves at night to shower unsuspecting larger mammals, often mountain tigers or goats, with their narcotic moth dust; then slowly dragging them back to their cave where they can be slowly fed upon by the colony. Because of the extreme efficiency of the archaea bacteria rich fluid all Yamato moths use for digestion and methane production, they can eat the meat even after it begins to rot without repercussions. However, they tend to put the carcasses of their prey out to freeze if the air grows cold enough to preserve them. Due to their severely barbed, long tongues, they can easily lick even frozen flesh off the bones of their meal. In spring, too, they rely more on meat than plant matter. Only in summer, when the first crop of nantama fruit is ready, do they switch back to primarily eating the nourishing yellow orb that usually grows near their lairs.

Sensô moths are least affected by the change of the seasons due to their existence as artificially bred creatures. They grow more lethargic in winter as their metabolism slows down, which is a remnant of their murasaki moth ancestors, a quality that wasn't bred out of them as their reduced food intake was beneficial for their keepers.

Additional Information

Domestication

Murasaki Moths Everywhere

Almost no animal is as beloved in the Yamato Kingdom as the murasaki moth, which was declared the national animal in 920 GE. The creature was first domesticated when the Yamato people began to settle down in the Yamato Valley. Transitioning from a nomadic lifestyle to a sedentary one around 4150 FA, attempts at domestication of murasaki moths were undertaken sporadically but took several years to actually work.Today there are two kinds of domesticated murasaki moths: murasaki moths as pets, and murasaki moths as livestock.

Murasaki Moths as Pets

The gentle murasaki moth is so passive and docile that the Yamato people have grown accustom to keeping them as pets. Their thick, soft fur makes them rather cuddly, and their bright colors are beautiful to behold. Children are often very fond of family moths, and there are regular beauty contests between moth enthusiasts in the Kingdom, where the fur patterns and other aspects are compared and rated. Many tools for moth care have been developed and are sold in any larger city of the Yamato Mountain Range.

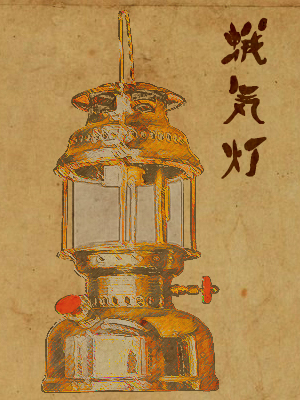

A moth care set, ca. 230 GE. From top to bottom, the lables read: teihakutsume-ma 停泊爪磨 ("mooring claw file"), enyu 艶油 ("luster cream"), en'genade 艶毛撫 ("luster brush"), ga'te-irebako 蛾手入れ箱 ("moth care set") - note: the box has the character "moth" inlaid in golden color, kesen 毛染 ("fur dye"), kenade 毛撫 ("fur brush").The luster cream is worked into the fur using a soft luster brush, which makes the moth's body and wing patterns shine. A mooring claw file is required to care for the mooring claw, as the moths usually whet it on rocky surfaces in the mountains. Usually, moth owners will dull the claws as much as possible so the moths cannot accidentally hurt anyone. An expensive moth care set is also considered a status symbol as I have learned during my time in the Yamato Kingdom, where wealthy families will casually display both their well-groomed moths and the intricate moth care set boxes, inlaid with gold and gems. I have also been told that regular brushing keeps the moth dust out of the fur, which can dull its sheen, and that the moths enjoy the brushing sensation, sometimes nuzzling the person taking care of them.

Uses, Products & Exploitation

Everywhere.

Murasaki Moths as LivestockThe moths have been kept and bred as livestook for millenia, which has pronounced some traits in their domesticated versions. Their fur is thicker and suited for sheering to make cloth, their metabolisms are slightly faster than their wild counterparts, which allows for more steady siphoning of methane gas from their floating bellies, a substance utilized for gas lamps. Murasaki moth arm flesh and floating belly lining are also ingredients for popular dishes in the Yamato Mountain Range, and moth dust, antennae, claw powder, and wing strut powder are used in some Yamato remedies. The moth dust is also prepared chemically as a powdered flavoring for tea and some dishes.

The Mighty Sensô Moth

Despite its name, the sensô moth, a special type of moth that was selectively bred from murasaki moths, was not initially intended as a war beast. The moths were grown larger and larger to yield more fur and gas and potentially more meat, though that last one did not work out in any significant manner.In time the moths were utilized as mounts, though not for combat but to deliver messages and sometimes passengers throughout the difficult terrain of the Yamato Mountain Range and rarely to the Middle Lands. Only during the Age of Heroes did the Greenhorns train and enhance their sensô moths to serve as aerial mounts in combat. The warriors would fly above the enemy troops and shoot with firesticks, drop explosive payloads, or jump from a deadly height, using a Greenhornish Megalance, a terrifying technamagic weapon that could gut an entire army troop in half if employed successfully.

Sadly, the large, methane-filled floating bellies of the moths proved to be susceptible to high tier lightning magic, which the Angel smiths began to work into their magical weapons more and more frequently, and the sensô moths were nearly driven into extinction by relentless attacks and extermination campaigns by the Old Gods and their subjects.

Today only one family in the Yamato Kingdom still keeps sensô moths, and the secrets of their care are tied into their iemoto 家元 ("The system by which the secrets of an art are passed along within a family or clan, passing from leader to leader").

Taming Demons

The terrifying yarenma moth seems like a very unlikely candidate for domestication or even hunt since it specifically adapted to repel humans, comatizing them with their moth dust if they come too close and then eating them alive. Naturally, one may think that all these monstrous creatures have to offer are nightmares, but the matter of the fact is that narcotics have had many uses throughout the ages, and as such the yarenma moth dust is actually a highly valued commodity.The substance is highly regulated in the Yamato Kingdom and unlicensed hunters that try to collect Yarenma moth dust, a perilous undertaking that yields high casualty rates, are ruthlessly persecuted.

The crux of the matter is that when compacted into resin, the yarenma moth dust can be used to create a very potent and addictive drug simply called moth dust, which is created and sold by the Black Market, which is rooted in Yamaseki (and previously was in the old capitals). The imperial family has tried fighting this with regulation but has been less than successful so far, the reason being that the dust is also caught and utilized to create many potent medicines, making it easier for criminal activities surrounding it to slip through the cracks.

During the Age of Awakening, yarenma were also sometimes caught in elaborate installations and used to gruesomely execute enemies of the state, who were fitted with wet cloth masks to resist the moth dust long enough for the creature to gouge the flesh from their living bodies using its deadly, barbed tongue. The animals were starved for this purpose. Today, the practice is illegal and no longer being continued officially, but rumors say that the Black Market still has one or two moths stowed away in the Uramachi of Yamaseki (the city behind the city).

To return to a lighter subject: cloth made from yarenma fur is quite beautiful due to its vibrant colors and much coveted in the Yamato Kingdom and beyond, especially since it is an exceedingly rare and expensive commodity, owing to the severe danger of hunting yarenma moths. Only two families in the whole kingdom even know how to work the material properly.

Facial characteristics

Geographic Origin and Distribution

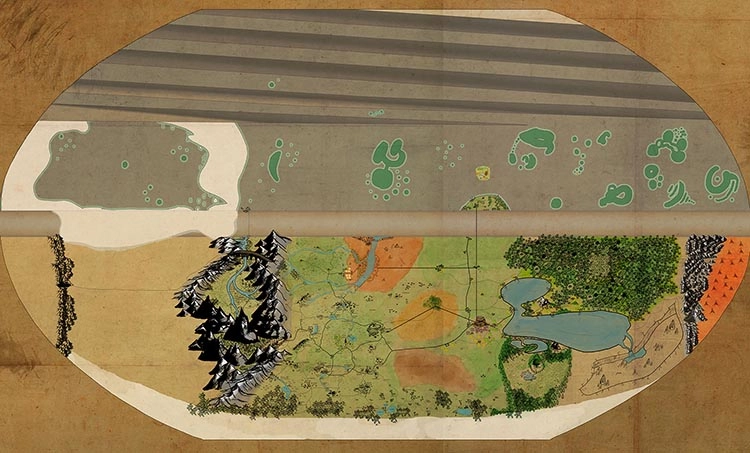

The following map of the Yamato Mountain Range is also a part of the Yamato-Ga-Daijiten 大和蛾大事典 ("The Great Encyclopedia of Yamato's Moths") and shows the habitats of murasaki moths, yarenma moths, and sensô-ga in the Yamato Mountain Range. Murasaki moths are indicated as pink, yarenma moths as purple, and sensô-ga as green; I have taken the liberty of adding corresponding illustrations. While the murasaki moth is spread throughout the entire mountain range in great numbers, yarenma populations are more scarce and regular extermination campaigns of the Yamato Kingdom keep them in check, though it is dangerous work. Sensô-ga were created through many generations of domestication and nearly went extinct during the Age of Heroes. A few escaped their captivity and actually managed to survive in the wild and their very small populations still live near the inner naraku no sôheki 奈落の双壁 ("Twin Walls of the Abyss") and in the kobayashi 巨林 ("Giant Grove").

Average Intelligence

Perception and Sensory Capabilities

Compound Eyes

Newer research shows that yarenma moths can actually see a broad spectrum of color, a trait that was likely developed to better see the nantama fruit it eats. While the large compound eye it possess in the center of its head has rod-type receptor cells and is largely responsible for its impeccable night vision and perception of contrasts, the four supplemental eyes it possesses each contain one type of cone-type receptor cell allowing it to see tetrachromatic images of its surroundings with well-defined depth perception.

The cone-type cells also exist in very small concentrations in the compound eyes of murasaki and sensô moths, but their color vision is very limited. While yarenma moths possess five compound eyes, one primary and four secondary ones, murasaki moths only possess two, and sensô moths four in total.

Multifunctional Antennae

While the YGD shows intricate diagrams of what they describe as funshokkaku 粉触角 ("Dust Antennae"), only their primary function of dust dispersal is discussed, likely because the science at the time missed or was incapable of detecting the fine haptic nerves in the antennae filaments, which can detect both changes in the wind and soundwaves.As a probably secondary effect of the adaptation of yarenma moths that has lead to larger and more numerous antennae that can distribute large quantities of dust at once, their air-tremor-perception is likewise improved significantly when compared to their murasaki moth brethren.

Symbiotic and Parasitic organisms

RPG Datasheet

Fate Core Cards

D&D 3.5 Monster Stats

Yarenma Moth

The yarenma moth is a feared omnivore that lives in certain cavernous slopes and cliffs of the Yamato Mountain Range. Though they generally eat nantama fruit where available, their barbed tongues are able to lick living flesh of animals, which are quickly rendered comatose by the yarenma moth's narcotic moth dust. In spring they eat small birds and in winter mountain lions and goats. Though not listed in their standard diet, human wanderers that stroll into their range are generally also on the menu.Combat

Yarenma moths will rarely attack creatures directly, though male yarenma moths sometimes have aggressive tendencies that may lead them to ignore this instinct. When attacking directly, the moths try to lick their prey with their dangerous, barbed tongues that can tear flesh from bone.Ordinarily though, the moth will attempt to stay out of sight or out of reach and shower the area in narcotic moth dust, waiting for enemies to fall asleep. When they do, the moths will either flee or start licking flesh off their victims, who quickly turn comatose and unable to wake up.

Narcotic Moth Dust (ex)

A yarenma moth can vaporize large quantities of highly narcotic dust from its many antennae and further proliferate it through the area using methane from its floating belly. Releasing the dust the first time in an encounter requires a standard action, after which it spreads in a 15-ft radius in the first round + 5-ft every round thereafter.

Creatues in range must succeed on a DC 13 fortitude save every turn or fall asleep. This does not affect vermin, undead, constructs, unconscious creatures, and creatures immune to poison. Saving throw bonuses that apply against poison apply against this attack.

Sleeping creatures are helpless. Slapping or wounding awakens an affected creature once it is no longer inhaling narcotic dust, but normal noise does not. Awakening a creature is a standard action (an application of the aid another action).

Sleep does not target unconscious creatures, constructs, or undead creatures.

Every additional yarenma moth using this attack in the same area increases its DC by 1 instead of requiring an additional saving throw.

Rend (ex)

A yarenma moth can apply 2d6 +2 (str based) rend damage in addition to its sting damage once an enemy is helpless and can be grasped by its small hands.

Low Body Density

Counts as one size category smaller when determining the effects of wind (see DMGI p.92 table 3-24 Wind Effects).

Skills

A yarenma moth has a +4 racial bonus on Tumble and Listen checks as well as a +2 racial bonus on Move Silently.

| Name | Yarenma Moth |

| Size/Type | Medium Vermin |

| Hit Dice | 2d8+4 (16) |

| Initiative | +8 |

| Speed | 20ft fly (perfect) |

| Armor Class | 17 (+3 natural, +4 dex) |

| Base Attack/Grapple | +2 / +4 |

| Attack | Sting +4 (1d2) |

| Full Attack | Sting +4 (1d2) |

| Space/Reach | 5ft. / 5ft. |

| Special Attacks | Narcotic moth dust, rend 2d6 +2 |

| Special Qualities | Scent, Darkvision 60ft., blind sense 120ft, low body density |

| Saves | Fort: +5, Ref: +4, Will: +0 |

| Abilities | Str: 15, Dex: 18, Con: 14, Int: -, Cha: 16, Wis: 10 |

| Skills | Tumble +6, Listen +8, Spot +2, Intimidate +4, Move Silently +8, Hide +6 |

| Feats | Alertness, Improved Initiative, Stealthy, Toughness |

| Environment | Temperate to sub-tropic mountain forests and mountain caves |

| Organization | Single, swarm (2-4), or colony (8-16) |

| Challenge Rating | 4 |

| Treasure | - |

| Alignment | Always neutral |

| Advancement | 2-5HD (Medium) |

| Level Adjustment | - |

![[Moth Anatomy] Moth Wings.jpg](https://www.worldanvil.com/uploads/images/e60e8e2326843debafb6ae7bb95d3b57.jpg)

![[Moth Anatomy] Wind Sacks.jpg](https://www.worldanvil.com/uploads/images/4f2456d50a1c9e9043179d14d1a041f3.jpg)

![[Moth Anatomy] Dust Antennae.jpg](https://www.worldanvil.com/uploads/images/809a1b283dea2f21afbe3d9000027195.jpg)

![[Moth Anatomy] Floating Belly.jpg](https://www.worldanvil.com/uploads/images/ffe06dd452349783114037b6bf89f018.jpg)

![[Moth Anatomy] Impregnation.jpg](https://www.worldanvil.com/uploads/images/cdae0e35d0e1c923a1484d2ef388afeb.jpg)

![[Moth Anatomy] Impregnation 2.jpg](https://www.worldanvil.com/uploads/images/937742993808f838c15530b4e15ec5af.jpg)

![[Moth Anatomy] Compound Eyes.jpg](https://www.worldanvil.com/uploads/images/5db38ea3c98dd2a19db9fc7573e13389.jpg)